“We are already in the frontline” – Sustainable value creation and entrepreneurial orientation in forest-based small and medium-sized enterprises

Rusanen K., Hujala T., Pykäläinen J. (2026). “We are already in the frontline” – Sustainable value creation and entrepreneurial orientation in forest-based small and medium-sized enterprises. Silva Fennica vol. 60 no. 1 article id 25001. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.25001

Highlights

- Sustainability transitions call for new types of businesses and value creation

- Sustainability-oriented forest-based SMEs providing various services were studied

- Operating environment and entrepreneurial orientation of companies shape how sustainable value is created with and for stakeholders

- There is resistance from the operating environment towards sustainability-oriented businesses

- System-level changes and sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship are interconnected and support each other.

Abstract

Sustainability challenges such as climate change and biodiversity loss have a great impact on the operating environment of companies. Business actors have increasingly sought answers to these challenges. A range of innovations, technologies and business models have been developed. Little is however known about those companies and entrepreneurs that strive for solving sustainability challenges. Sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship has interested researchers for a while. Nevertheless, studies have not thoroughly focused on forest-based services and related business models and value creation. This multiple case study investigates how the operating environment and entrepreneurial orientation are entailed in sustainability-pursuant value creation. We interviewed nine sustainability-oriented small and medium-sized enterprises providing forest-based services. The results indicate that the companies feature several entrepreneurial capabilities that enable them creating sustainable value. They are positively oriented towards future and consider their business as a solution to focal sustainability challenges. The companies’ operating environment can support the emergence and long-term development of sustainability-oriented businesses and innovations, and hence collaboration with stakeholders is essential for sustainable value creation. However, the established forest-based sector and existing support system have created tensions for the development of the sustainability-oriented businesses. The companies strive actively for making an impact on their operating environment to create sustainable value with and for their stakeholders. This study advances empirical research on sustainable value creation and entrepreneurship. Overall, this paper suggests that sustainability-oriented entrepreneurs need more collaboration and support for scaling up the solving of sustainability challenges.

Keywords

forest-based sector;

sustainability transition;

sustainable business model;

sustainable entrepreneurship;

value creation

-

Rusanen,

School of Forest Sciences, Faculty of Science, Forestry and Technology, University of Eastern Finland, P.O. Box 111, FI-80101 Joensuu, Finland

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1705-5561

E-mail

katri.rusanen@uef.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1705-5561

E-mail

katri.rusanen@uef.fi

-

Hujala,

School of Forest Sciences, Faculty of Science, Forestry and Technology, University of Eastern Finland, P.O. Box 111, FI-80101 Joensuu, Finland

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7905-7602

E-mail

teppo.hujala@uef.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7905-7602

E-mail

teppo.hujala@uef.fi

-

Pykäläinen,

School of Forest Sciences, Faculty of Science, Forestry and Technology, University of Eastern Finland, P.O. Box 111, FI-80101 Joensuu, Finland

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3427-9954

E-mail

jouni.pykalainen@uef.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3427-9954

E-mail

jouni.pykalainen@uef.fi

Received 7 January 2025 Accepted 20 December 2025 Published 13 January 2026

Views 8281

Available at https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.25001 | Download PDF

Supplementary Files

1 Introduction

Sustainable development has been an ambitious endeavour for decades while requiring more sustainable production and consumption patterns. The quest for sustainability transition refers to the change of established socio-technical systems towards more sustainable (Markard et al. 2012). The role of companies in this transition is essential: while they are causing many of these problems (CDP 2017), they are in a pivotal position to solve them together with other societal actors (Loorbach and Wijsman 2013; Scheyvens et al. 2016). In addition to energy and resource efficiency (Caidado et al. 2017) as well as corporate responsibility (Barnett 2019), business models and value creation have been considered vital for sustainability transition (Lüdeke-Freund 2010; Boons and Lüdeke-Freund 2013). Sustainable value creation enables companies contributing positively to the natural environment and society through their business activities (Hart and Milstein 2003; Dyllick and Muff 2016; Evans et al. 2017) whilst considering the needs of multiple stakeholders (Upward and Jones 2016; Freudenreich et al. 2020). Sustainable value can entail forms of environmental values such as renewability of resources, low waste and high biodiversity, social values such as community development, health and safety, and economic values such as profits, return on investments and business stability (Evans et al. 2017).

Sustainable entrepreneurship has been recognized as a major conduit for sustainable products and processes and thus considered an answer to many social and environmental concerns (Hall et al. 2010). Hence, sustainability-oriented entrepreneurs “…bring forth sustainability innovations that convert market imperfections into business opportunities, replace unsustainable forms of production and consumption, and create value for a broad range of stakeholders” (Lüdeke-Freund 2020). Innovations for sustainability refer to radically new or incrementally improved products, services, or systems which lead to environmental and/or social benefits (Bocken et al. 2019, p. 22). Sustainability-oriented entrepreneurial activity can also be found in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs), including start-ups, entrepreneurs and micro firms. SMEs feature less than 250 employees and turnover smaller than MEUR 50. In comparison to larger companies, SMEs are considered more capable of enhancing radical innovations (Schaltegger and Wagner 2011). SMEs can produce innovations for sustainability with their agile business structures and entrepreneurial management styles (Bos-Brouwers 2010). They can create value in novel ways (Sinkovics et al. 2014) whilst not being tied to specific resources, assets, capabilities, and business models like mature and large companies (Tripsas and Gavetti 2000; Markard et al. 2012; Bidmon and Knab 2018). Furthermore, the skills and competencies of personnel enable SMEs to discover and exploit new opportunities better than large companies (Shane 2003). Thus, it has been argued that SMEs might see sustainability challenges as a business opportunity instead of an external threat (Jansson et al. 2017).

Hence, business strategy and management research has investigated those companies that have been “…established with explicit strategic intent to operate in a sustainable manner from the outset” (Knoppen and Knight 2022). The literature has used terms such as environmental entrepreneurship, ecopreneurship, green entrepreneurship, or social entrepreneurship (Sharir and Lerner 2006; Dixon and Clifford 2007; Meek et al. 2010; Demirel et al. 2019) to describe such companies. Sustainability-oriented companies consider economic performance as a necessary condition and emphasise environmental and social value creation (Knoppen and Knight 2022). Furthermore, those companies verify their sustainability performance through reporting and certifying (Ostermann et al. 2021) instead of considering sustainability only a marketing strategy.

Some of the SMEs’ motivation for creating sustainable value could stem from their entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurial orientation is seen to consist of innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking (Miller 1983; Covin and Slevin 1989), which have all been addressed when assessing entrepreneurship (Andersén et al. 2015). Entrepreneurial orientation also refers to companies’ abilities to explore and monitor their micro and macro environments (Andersén et al. 2015) and seize observed opportunities (Cullen and De Angelis 2021). However, these abilities do not always lead to business success (Wales 2016). Entrepreneurial orientation does not necessarily connect to the whole business of a company, but to a specific area, such as marketing (Keh et al. 2007), internationalisation (Kuivalainen et al. 2007; Gabrielsson et al. 2025), value creation (Andersén et al. 2015), or sustainability (Amankwah-Amoah et al. 2019). Hence, there is an abundance of studies related to sustainable innovations created by companies (Hossain et al. 2018). In these studies, proactive companies are those capable of finding new business opportunities from sustainability (Aragón-Correa et al. 2008; Jansson et al. 2017). Risk-taking, in turn, can help companies to try, e.g. new sustainable technologies (Zhai et al. 2018). Furthermore, there are studies confirming that entrepreneurial orientation affects SMEs’ sustainability performance (Roxas et al. 2017). Hence, entrepreneurially oriented SMEs commit to sustainability more than those not entrepreneurially oriented ones (Jansson et al. 2017). Entrepreneurial orientation has also been associated with developing circular business models (Cullen and De Angelis 2021) through which sustainable value can be created.

So far, there is little empirical research on sustainability-oriented SMEs and entrepreneurship (Knoppen and Knight 2022; Das and Bocken 2024). Research on entrepreneurial orientation has mainly focused on theorising or quantitatively studying the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and sustainability performance. These studies tend to focus on environmental aspects whilst lacking a systemic perspective on sustainability (Klewitz and Hansen 2014). Furthermore, there is little research on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and value creation (Andersén et al. 2015; Criado-Gomis et al. 2020), especially with the focus on sustainability (Cullen and De Angelis 2021; Alcalde-Calonge et al. 2022). So far Alcalde-Calonge et al. (2022) have argued that the level of circularity of the business model yields from both internal factors such as entrepreneurial orientation and external factors including social/cultural, technological, regulatory and economic/financial dimensions. However, empirical research on such a relationship is lacking, especially from natural resource-based industries (Konietzko et al. 2023), such as the forest-based sector.

Sustainability transition has been addressed within the Finnish forest-based sector (Näyhä 2019). The forest-based sector comprises the pulp and paper and wood processing industries as well as other companies utilising forest-based resources. Since the establishment of the term forest-based bioeconomy, the sector includes companies outside the conventional sector, such as food, pharmaceutical, chemical and clothing companies (Näyhä et al. 2014). Especially in Europe, the pressures on using forest-based resources have been increasing. Thus, new laws and regulation regarding standards and certifications are emerging (Regulation (EU) 2023/2772). The new regulations challenge companies to consider their business models and strategies toward holistic sustainability. However, it seems that the large companies in particular are struggling with the sustainability transition (Laakkonen et al. 2023), whilst trying to maintain prevailing business models, networks, and practices. Hence, expectations have been appointed to SMEs (Näyhä et al. 2014), These companies could be key actors in transforming the sector towards a more sustainable model (Haldar 2019; D’Amato et al. 2020). Furthermore, service-based businesses have appeared appealing in this development (Näyhä 2019). Some sustainability-oriented SMEs providing forest-based services have already emerged in the sector. However, research on forest-based companies has focused on large companies, and thus empirical investigations on sustainable entrepreneurship as well as sustainable value creation are limited (D’Amato et al. 2020; Rusanen et al. 2024). Furthermore, little is known of the entrepreneurial processes behind such business models. Such understanding could also benefit large incumbent companies in creating new sustainable services. Hence, this study tackles this research gap by providing understanding on the evolving operating environment and entrepreneurial-orientation of sustainability-oriented SMEs in the creation of sustainable forest-based value.

Our research questions are formed as follows:

RQ1: How do forest-based companies perceive the role of the operating environment in their value creation logic?

RQ2: What kind of relationship can be found between the forest-based companies’ entrepreneurial orientation and value creation logic?

RQ3: How do the forest-based companies create sustainable value with and for their stakeholders?

This multiple-case study presents nine Finnish forest-based SMEs offering various sustainability-oriented services new to the forest-based sector. The data are collected through qualitative interviews. The study contributes to the literature and theories of strategic management, hence emphasising entrepreneurial orientation from sustainable business model and value creation perspectives. Furthermore, the study has roots in the sustainability transition research, which considers business to be central actors in shaping the markets towards a more sustainable model (Loorbach and Wijsman 2013). In managerial level, this multiple case study provides empirical examples of sustainability-oriented service-based companies, implementing sustainable value creation which can serve as an inspiration to other business managers and entrepreneurs.

2 Material and methods

This study follows a qualitative, multiple case study methodology (Yin 2014). The case study was seen as an appropriate research method to create deep and detailed understanding of the phenomenon in a real-life context (Corbin and Strauss 2014) – sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship and sustainable value creation within the forest-based sector. Multiple-case studies are common in business management research where they have mainly supported conceptual development rather than statistical generalisation of results (Eriksson and Kovalainen 2015). Whilst providing conceptual knowledge on sustainable value creation (Lüdeke-Freund 2020; Rusanen et al. 2024), a multiple-case strategy also enables investigating each case in detail. Analysis of similarities and differences between the cases provides empirically grounded descriptions of sustainable value creation and entrepreneurship in a more generalizable manner (Yin 2014).

The data were collected through nine semi-structured interviews between January and April 2024. Qualitative interviews were considered a suitable method for the data collection, since SMEs tend to use varying language when discussing sustainability terminology (Klewitz and Hansen 2014). Thus, letting them speak more openly with their own expressions and interpreting the responses later in a common conceptual framework facilitates meaningful knowledge accumulation. In addition, semi-structured interviews were chosen due to their flexibility and ability to provide a profound understanding of the phenomena (Kallio et al. 2016).

Purposeful sampling (Yin 2016) was utilised in approaching Finnish sustainability-oriented SMEs companies for participation. Due to the difficulty of detecting the exact population of relevant companies, an online search was conducted with search words such as sustainability, restoration, carbon sequestration, forest, and business. This search yielded some 20 companies. Based on the selection criteria (Patton 2023): (1) each selected company had to include some environmental and/or social elements in the value propositions, and (2) the selected companies and their services had to represent different types of forest-based services. This was verified by investigating the companies’ websites. The sampling reached saturation point with nine cases, which was considered sufficient for such a multiple case study representing a variety of sustainability-oriented services. Thus, either no further relevant companies were detected or they did not wish to participate in the study. A full list of case companies interviewed is presented in Table 1. Most of the interviewees were CEOs or generally representing the managerial level.

| Table 1. Research sample of the multiple case study. | |||||

| Company | Sustainability-oriented service(s) | Founding year | Annual turnover, EUR (year 2023) | Nr of personnel | Interviewee position |

| 1 | Carbon sequestration | 2019 | 1000 | 2 | CEO |

| 2 | Carbon sequestration and restoration | 2020 | 55 000 | 4–5 | CEO |

| 3 | Carbon sequestration and environmental consultation | 2019 | 838 000 | 17 | Founder |

| 4 | Sustainable forest management/cooperative forest incl. continuous cover forestry | 2020 | 917 000 | 3 | CEO |

| 5 | Circular economy, recycled wood | 2023 | 57 000 | 6 | Innovation manager, Founder |

| 6 | Sustainable forest management incl. continuous cover forestry | 2007 | 784 000 | 6 | CEO |

| 7 | Giftshop for tree planting and nature conservation | 2021 | 143 000 | 2 | Vice president |

| 8 | Sustainable forest management incl. restoration services, continuous cover forestry | 2022 | 267 000 | 3 | CEO |

| 9 | Health services in forests | 2016 | 298 000 | 2 | CEO |

The interviews included (re: Supplementary file S1) three main themes: (1) company’s background information; (2) the company’s business model construct; and (3) views on their current and future operating environment. There was only one direct question on entrepreneurial orientation, which related to innovativeness, and the other elements, risk-taking and proactiveness, were listened for and queried with follow-up questions related to the business model construct. The questions were tested for clarity before the actual interviews, and anonymity for the interviewees as well as the companies investigated was secured.

All interviews were organised online as well as recorded and transcribed. On average, they lasted approximately 60 minutes. Additional notes were taken during the interviews to support the recorded data.

The transcribed data were analysed and coded using Atlas.ti software version 25.0.1 (2025). The data were analysed by using abductive logic (Dubois and Gadde 2002), meaning that instead of purely inductive (data-driven) or deductive (theory-driven) coding, a combination of those approaches was employed. To that end, literature and present research questions were used to develop initial codes (content categories) which included: sustainable value creation, i.e. value creation with and for stakeholders; entrepreneurial orientation related elements: innovativeness, proactiveness and risk-taking; and operating environment. Then, whilst systematically reading through the transcripts, the initial codes served as hints to filter relevant contents and assign those to suitable codes, while remaining open to contents that the data revealed without an explicit connection to any of the pre-defined coding categories. As a result, the eventual coding contained both conceptually interpreted (top-down) and openly observed (bottom-up) codes. The subsequent reasoning to answer the research questions was iterative in nature, allowing moving between data- and concept-based interpretations. Hence, based on the coding, the researchers aimed at describing, in a systematic and data-informed manner, how sustainable value creation is connected to the operating environment and entrepreneurial orientation. Furthermore, differences and similarities between the cases were considered whilst reflecting these to the findings from prior literature and thus providing conclusions in an iterative manner. The data obtained were triangulated with additional sources such as interview notes, company websites and prior literature.

3 Results

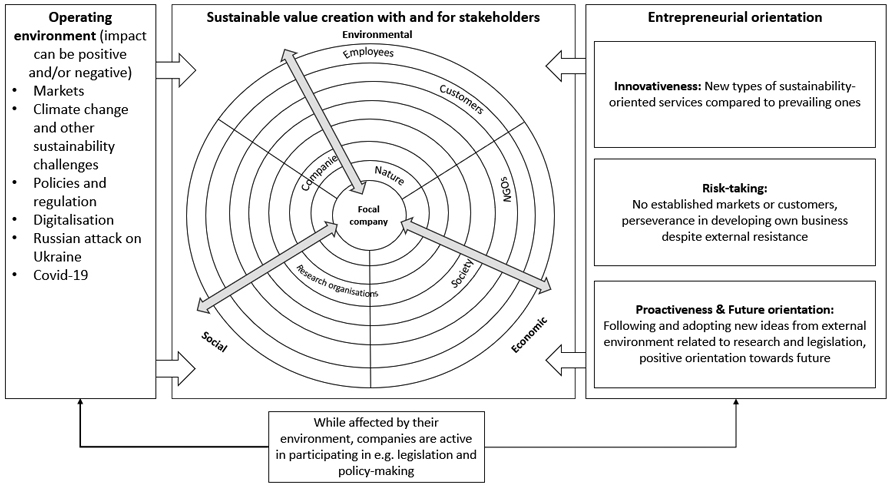

According to our results, the operating environment of a company and entrepreneurial orientation of the entrepreneur crucially affects the way how the company creates sustainable forest-based value with and for its stakeholders (Fig. 1). Changes in the operating environment, such as the progress of climate change and biodiversity loss and new legislation in European and Finnish levels, have created a push towards developing sustainability-oriented business. However, the companies have considered support from the markets and especially from policymakers and large companies inadequate. Simultaneously, the companies are to some extent innovative, risk-taking and proactive in creating sustainable value. Both the operating environment and entrepreneurial orientation are reflected in their sustainable value creation with and for their stakeholders. Furthermore, they can affect their operating environment and how sustainable value creation is supported through their entrepreneurial capabilities. A synthesis of the results is presented in Table 2 and results are elaborated thoroughly in the following sub-chapters.

Fig. 1. The relationship between SMEs’ operating environment, entrepreneurial orientation and sustainable value creation. The layers of the circle represent the most important stakeholder groups in no particular order, and the three sections represent environmental, social and economic value creation. The three grey arrows describe mutual processes of how value is created both with and for stakeholders.

| Table 2. A synthesis of the main empirical findings representing the relationship of the case companies’ operating environment, entrepreneurial orientation and sustainable value creation. | |||

| Findings | Citations | ||

| Reacting to operating environment | Current | Right timing for establishing sustainable business since expertise and resources are available Governments’ role has been mostly deteriorating for developing sustainable business Sustainability-oriented services are offered due to the demand of sustainable use of forests and related business Old established structures, practices, long value chains and actors in the forest-based sector have hampered the development of sustainability-oriented companies, yet such resistance has created a push towards creating sustainable value | “Then at wildest, on the IPCC report’s publishing day, 65 people donated [money for restoration activities]” (Company 3) “The role of the state now in utilising the carbon sink of Finnish forests, […]. That’s the biggest challenge.” (Company 1) “In service-based entrepreneurs and forest wealth management there has been a need for years to be able to create revenues through other ways, other than just wood-production.” (Company 3) “Transparency hasn’t been great in the forest sector, so we have brought transparency to economic value creation.” (Company 4) |

| Changes | Increasing sustainability regulation can enhance possibilities to create sustainable value but also can have negative effects Increasing sustainability challenges have and will create more demand for sustainable value creation Digitalisation has enhanced effectiveness Sudden changes such as Covid-19 and Russian attack to Ukraine considered as negative for business development, yet positive for nature | “We have to be able to advice our customers in the changing regulative environment, that everything goes right in terms of regulations and standards, […], we have to stay awake of what is demanded and which methods are used…” (Company 4) “What has helped, has been the development of legislation, and that’s a big thing for us that it has happened in Finland but also in EU level, they will go towards sustainable development […]” (Company 5) “Another big challenge is climate change. […] How can we adapt our services so that we can try to mitigate and limit it.” (Company 6) “We also have that [name of a service] forest information system and there AI-based tools, and you can analyse based on aerial photos where bark beetle damages are […]” (Company 8) “Then Covid-19 came and planes were left at airports, people were left at home, so then there was a clear decrease here in compensation. If compensation is done as a climate act, it is better to stop world with Covid - relative to climate.” (Company 2) | |

| Employing entrepreneurial orientation | Innovativeness | Innovative ways how sustainable value is created e.g., through enhancing carbon sequestration, restoring ecosystems, and strengthening human-forest relationship, that differ from the traditional forest-based sector and related services | “We thought up taking people to forest, […], so that there were a doctor, a physiotherapist and an occupational therapist involved giving guidance.” (Company 9) “Circular economy has been the main theme in the activities we do and to do it as nature friendly as possible. And so that no trees would have to be cut and put to energy use because of our activities” (Company 5) |

| Proactiveness & future orientation | Providing sustainability-oriented services in the front line while following development actively Oriented positively towards future and considering own business as a solution to sustainability challenges Contributing to sustainability legislation and regulation development Following actively related policy development and research | “Climate compensation and work for climate or revenue gained from it, has featured for a long time, and then when nothing started to happen, we got the idea that we have to figure it out by ourselves” (Company 3) “[…] whether it is EU-policies, or private forest owner who starts to dig ditches to peatland […] I do believe that there is even more demand for our message and idea.” (Company 6) “This change in legislation in continuous cover forestry, in which we were quite strongly involved in the background.” (Company 6) “Surprisingly big part is mapping and keeping up with this climate and ecological restoration related scientific information and topical information. It is actually quite an important activity and the whole group does it because everything cannot be reached by one person.” (Company 2) | |

| Risk-taking | No established markets or regulation for such sustainability-oriented business (can also result as value destruction) Developing services that challenge the current practices of the established forest-based business based on wood production Following own values considered as more important than economic gains Financial risks minimised | “And then another risk is that this cooperative forest concept doesn’t break through and this [own business] will remain as… this is an ok business for us, but this is still marginal in terms of the forest sector” (Company 4) “We have security of supply and transparency, of which I am proud of and have been criticised by some large companies” (Company 8) “Even if it was from one meter away and the cheapest contractor, but saying that they don’t understand our activities, […], we then take double times more expensive one from 5 meters away who understands and shares same value base as us.” (Company 7) “We excluded ourselves with the sustainability thinking, so that our activities are verified by anyone from nearby and from further too, so we excluded ourselves from such large sales potential.” (Company 7) | |

| Considering and engaging stakeholders | Stakeholder networks consist of actors with similar values e.g., other companies, customers, research organisations, universities, non-governmental organisations with and for whom sustainable value is created Customers and other companies in central role and with whom environmental and social value is created: customers e.g. creating demand and paying for the sustainability-oriented services, other companies e.g. executing the environmental operations, supporting rural development and ensuring transparency Environment as main stakeholder for which value is created. Forest owners and other customers as main stakeholder groups for which new alternative sustainability-oriented services are provided | “With all these activities we create forest where climate sequestration, biodiversity and recreational values are combined well.” (Company 4) “Forestry associations are partners for us, and they take care of exactly the forest owner phases, for example you need to verify the tree stand before the project” (Company 3) “Restoring nature values as a compensation possibility is our product” (Company 2) | |

3.1 How the forest-based companies perceive the role of the operating environment in their value creation logic (RQ1)

3.1.1 Current operating environment and stakeholders

All companies described the operating environment differently due to their type of business; however, similar themes also emerged. Most of the companies’ stakeholder networks consisted of similar actors: research organisations and universities, governmental organisations, different sized companies, forest owners, cooperative forests, forest owner associations and other non-governmental organisations. Several interviewees mentioned collaboration as crucial for their value creation, and some were active in their regional networks. Hence, they tended to cooperate with stakeholders sharing similar values. Competition was mainly described as positive, though the competition related to wood production services was considered tighter. Most of the companies had found their own niche markets where no tight competition existed.

Case companies operating within the carbon sequestration business and one company operating within the gift shop business were also operating within international markets. The impact of the Finnish forest-based sector dominated by the three large pulp and paper companies, UPM, Stora Enso and Metsä Group, was considered great to the operating environment. Namely, these companies affect e.g. competition, prices and legislation. Negative aspects were emphasised by both those case companies operating within the wood production related business and those outside it. Furthermore, large international companies related to carbon sequestration services were mentioned as a threat to the development of sustainable business. It was acknowledged that the past forest management scheme in Finland has been unsustainable with overly excessive harvests. The forest-based sector was described as untransparent and conservative, which tends, according to one case company: “…to take the easy way out”. One interviewee described the sector as follows:

“I found the forest sector very static, conservative and not so agile. So we have had certain actors and certain procedures and certain ways to act for 100 years and then we sort of go with the same ones. And all service, customer service and marketing and other stuff has been in its infancy in the forest sector compared to others, in my opinion.” (Company 3)

The business must be extensive enough to convince the large companies as well as funders. Thus, for some of the case companies it was easier and more profitable to operate directly with forest owners and consumers. Simultaneously, companies had received positive feedback from outside the forest-based sector.

The Finnish government plays an important role in the operating environment, though several companies regarded it as hampering business development. According to some companies, the EU consequently exerted a stronger role in policymaking and governance. Other European countries, such as Sweden and Germany, were described as more progressive. From legislation, the Forest Act was mentioned as having the most impact. Until 2014, other than even-aged forest management was prohibited in Finland, and since revising the Act, several companies had benefited from the possibility to practice continuous cover forestry. Legislation is still under development for those case companies that operated within new markets or services. Interviewees were of the view that the current regulation insufficiently supports their circular economy solutions and business with ecosystem services, other than wood production. For the case companies which engage in business related to carbon sequestration and ecological compensations, the regulatory environment in Finland was seen as demanding. They subsequently noted that the business cannot be further developed, due to the double accounting that the Finnish government has been applying. In other words, they said that the business cannot be developed unless the Finnish government stops including the private forest owners’ carbon sequestration count in the national calculations.

3.1.2 Changes in the operating environment

All case companies had experienced changes in their operating environment. They considered the changes mostly positive, thereby offering them momentum to establish the business and thus create sustainable value. The changes in the forest-based sector were described as radical, due to changes in legislation. In particular, sustainability challenges such as climate change had affected most of the companies’ operating environment, as one interviewee points out:

”Well, perhaps in our sector [forest-based sector] and in general sustainable development needs resulted. And the change in human level, in humans and organisations and their activities it is indeed in a way taken into consideration today in everything, and therefore more services are needed. That is the greatest driver.” (Company 3)

Sustainability regulation had increased and applies to all kinds of companies today. Company 2 considered the updated Environmental Protection Act as important to their value creation. Hence, there had been more political pressure to develop sustainability-oriented business. Due to diminishing natural resources, prices of forest holdings and wood had risen. This was considered positive, since then wood as raw material is valued by society. Hence, increasing awareness of sustainability challenges had created more demand for the case companies’ services and related value creation. The forest-based sector has evolved slowly, which could be detrimental to such sustainability-oriented companies’ development. One interviewee noted:

“These changes in the forest sector are so slow and often so rigid that somehow we are hoping such revolution would happen, but if it doesn’t happen, it will lead to a point where our business will grow only so moderately, as this far it has. We are doing fine of course, but it will not become a huge success story.” (Company 4)

Simultaneously, case companies creating value for forest owners mentioned how forest owners’ attitudes and behaviour had not changed drastically, which could retard the demand for such services. Furthermore, the past Finnish governments have changed their opinions on the policies regarding forest-related carbon storage, which had also affected some of the companies. For instance, during the previous government, municipalities had to create plans for climate change mitigation, which was beneficial for the related case companies.

Other changes had also been detected. The development of digitalisation and open national forest inventory data had affected many businesses positively, especially through decreased costs. For a few companies, the negative impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic and Russian’s aggressive war in Ukraine had been more severe than to others. In particular, wood prices had increased, due to the decrease of imported wood from Russia. For Company 5, this had resulted as difficulty in supplying the recycled wood they used in their value creation. An interviewee from Company 7 operating within the gift shop markets explained that during challenging times customers had donated to charity, which resulted as less money spend on gifts – in this case, planting trees. During the pandemic, people were flying less and therefore not compensating their flights, which had resulted in less restored ecosystems (Company 2). Hence, changes in the operating environment could be negative for businesses, but positive for the natural environment. Thus, most of the case companies were adaptive and offering several services that could be developed during various time periods.

3.2 The relationship between forest-based companies’ entrepreneurial orientation and value creation logic (RQ2)

For some of the case companies, motivation for doing business overall stems from environmental and social challenges and the desire to resolve them. According to one interviewee:

“[…] biodiversity and climate-related effectiveness is the primary motive for the business, so that we obtain impact there and really make things – visible things – happen, and the second is maybe the extent of the business or growth or other…”. (Company 3)

Another interviewee stated that: “…as long as the salaries can be paid, the goal is to restore ecosystems as much as possible.” (Company 2). Company 6 wanted to change the contemporary forest management scheme more diversely, from even-aged to continuous cover forestry; thus providing new services for forest owners. A couple of case companies were keen on developing non-wood production-related services for forest owners, thus transforming the sector in a more versatile direction as well as making it more service- and customer-oriented. Hence, for Company 8, entrepreneurship itself was the main ambition – particularly since employment in the forest-based sector had been unstable and sub-contracting underpaid. Overall, personal values were considered as essential for developing one’s own business, as concluded by one interviewee:

“Well, the motivation for founding the company was that we’re able to operate out of the mainstream. Because it forces you to think certain way. Then you can’t do what you want to do from your own value premises.” (Company 9)

Some of the case companies did not wish to expand their businesses, thus keeping the business self-sufficient. On the other hand, for some of the companies, economic benefits – either personal or those of the forest owners – were considered important in founding the businesses. One interviewee concluded:

“[… ] For years there has been a demand to be able to create income other ways than only through wood production, …,well, nevertheless this climate compensation and work for climate or income gained from it has been topical, and once it didn’t start to evolve, we got the idea that we’d have to solve it by ourselves…”. (Company 3)

They were thus seeking to gain a competitive advantage from sustainability. Two interviewees were looking into developing an “exit plan” through their business, i.e. planning to get their business sold within the next few years while being able to retire from daily work life. However, two interviewees had already retired from everyday business life and had more of a social drive to develop the business.

3.2.1 Innovativeness

In general, the case companies investigated have adopted innovative and sustainable business models and value creation, compared to the prevailing ones in the Finnish forest-based sector. These include, e.g. restoration services, a nature-based gift shop including forestation and conservation services, as well as continuous cover forest management and carbon sequestration services. Company 4 was enhancing sustainable, long-term and data-driven management of the cooperative forest, which in Finland has traditionally focus on intensive harvests and economic profit for the members. Company 5’s business related to charring recycled wood materials was completely new in the Finnish markets and also differed from those abroad with more sustainable processes. Thus, most of the businesses had not mainstreamed in the traditional sector, even though they have been discussed actively among scholars and practitioners. The case companies aim to tackle various sustainability challenges through their business, whilst especially considering environmental aspects of forests at the core of value creation. Other Finnish and international companies had adopted their pioneering, innovative procedures. The perspective of value co-creation overall has not been adopted widely in the forest-based sector, and hence several of the case companies have put customer needs in the focus. Intangible, human-nature relationship-related services are still new to the sector and were presented by two case companies, Case 9 focusing on direct healthcare service in forests and Case 7 on a tree-planting giftshop. Several interviewees wanted to develop something new compared to the prevailing innovations, products and services in the sector, and were subsequently adopting and developing new methods and tools. Furthermore, Company 8 was developing alternative ways for value capture, i.e. to fund nature management and restoration activities with finance institutions.

3.2.2 Proactiveness

The case companies have been proactive in creating their sustainable businesses in the frontline and have hence seen possibilities arising from sustainability and believing that demand for them could emerge in the future. One interviewee stated:

“The same way these nature values and other issues will mainstream little by little, but following the speed of change, we will have competitive advantage for decades.” (Company 6)

Most of the case companies aspire to and have been pioneers in creating sustainable value within their business field. Several case companies considered the increasing legislation and regulation related to sustainable natural resource use beneficial for their value creation. One interviewee concludes:

“If such restoration targets are initiated from EU, […], if they turn on the money taps and billions will be provided, then there will be a significant future niche in the markets. So that’s why we’ve started to make the basis ready.” (Company 8)

New funding sources and instruments for developing their sustainability-oriented services can emerge from EU related, for instance, to ecosystem restoration. Companies had started to develop their procedures and systems for the future legislative changes. Company 3 was already following EU’s taxonomy, even though they had not yet applied for related funding. Case companies creating value related to restoration have been proactive since the legislation has been recently finalised (Regulation (EU) 2024/1991), after a long period of planning and contestation. Company 2 has been taking part as an advisor in related decision-making in Finland. Those case companies providing carbon sequestration-based services and continuous cover forestry have been one of the first companies providing such business in Finland, and have contributed to developing the regulation and development of the standard scheme for carbon markets. One interviewee emphasised their proactiveness:

“Perhaps we entrepreneurs are already in the frontline in a way this society is not; this legislation has not been able to join it.” (Company 1)

Company 7 provides a service for people who have lost their relationship with nature, since there could be a demand for such business in the future. Most of the case companies were offering several services to balance the variation in demand and supply. Finally, they also followed research and other trends actively, from which they may gain new ideas for creating sustainable value.

3.2.3 Risk-taking

The case companies have been courageous in developing sustainable business that has been new in the forest-based sector and in the markets in general. No great demand or established markets for such services to date have existed. Therefore, the companies have taken considerable risks in founding their sustainable businesses, whilst also operating within an established sector with path-dependencies. Most of the case companies had experienced resistance from the forest-based sector and related actors. For Company 5, resources were obtained from, among others, large sawn wood manufacturers that had first considered the circular business idea too risky. The interviewee stated:

“The large Finnish forest companies have said exactly the same: that it [the business they have developed] is not possible, […]; in a way, those old attitudes are there to hold things back, but we have not given up and instead have told them [forest companies] that it is possible.” (Company 5)

Company 8 transparent pricing had received criticism from the large companies:

“We are secure of supply and transparency, of which I am really proud, but we have also received criticism from certain large corporations. Have you looked at our website? But the price list there is very openly available, concerning which I once got some feedback from a larger forest company.” (Company 8)

Hence, the companies had to be rather perseverant in developing their sustainable business and push through several obstacles. Company 5 had turned down a large deal, since they would have not been able to comply with their sustainability standard which represented their values. On the other hand, Company 2 did not use any certification schemes, due to which they had lost some large deals. They considered them as expensive and lacking credibility: thus, they used their own auditing procedures.

Contrary to risk-taking, most of the case companies have not taken any large bank loans, subsequently not taking financial risks in developing their businesses. On the other hand, one company had not been able to obtain a bank loan due to overly minimal turnover. Furthermore, several companies had kept their number of personnel small, due to plausible risks. Thus, it was more important for them to continue maintaining the sustainable business and not necessarily grow it.

3.3 Company views on sustainable value creation with and for stakeholders (RQ3)

3.3.1 Sustainable value creation with stakeholders

The case companies created sustainable value with their stakeholders in several means. Related to environmental value creation, customers were one of the main stakeholder groups and created the demand and paid for the sustainability-oriented forest-based services. For some of the companies, customers were also in a central position in experiencing the service, e.g. in enhancing the human-forest relationship:

“…through our service the customer understands her impact on the nature and hence the connection between nature and human wellbeing. People would really understand what kind of impact we have, so if we destroy this surrounding natural environment, then we will destroy our own health and our life too.” (Company 9)

Another important stakeholder group for environmental value creation was other companies. Forest operator companies or contractors conducted the physical operations in the forests including, e.g. restoration and planting. However, for some of the case companies it was essential that they practiced this independently, without external help to enhance transparency and quality of the work. Hence, using contractors could also result as value destruction if plans would be insufficient or otherwise not followed. Some case companies used auditing companies to verify sustainability, however, some companies practiced this independently since the external auditing system was considered as lacking credibility. Overall, other stakeholder companies provided important intangible or tangible resources in many of the cases (e.g. biogas, IT programmes or tree seedlings) for environmental value creation. Most of the case companies collaborated with universities and research organisations in developing their methods and processes related to environmental programmes and accounting/calculations. Forest owners were another important stakeholder group that enabled utilising the forest area for environmental or climate compensation. In Company 2, an environmental NGO was helping in finding forest sites for restoration activities. Furthermore, in some case companies, their own employees were in a central position to detect biodiversity rich areas in forests and applied environmental plans in practice, as expressed by one interviewee:

“[…] we have our own employees, professional Finnish people, professional loggers, who have years of experience, and they know the certificates and all…”. Company 8

Collaborating with other companies was also essential for social value creation. For example, auditing companies were enhancing the transparency of the business operations, some companies were providing social and governance expertise for sustainability reporting, and local contractors enabled recreational use of forests and provided local workforce, thus supporting local/rural development. One company participated in organising joint events related to enhancing human-nature relationships and another provided planetary food for the customers during the service. For case company 4, collaborating with competitors supported the overall development of the cooperative forests. Collaborating with research organisations enabled generating new knowledge for the use of others. Social value creation with forest owners related to providing their forests for recreational use and operating directly with them enhanced transparency. Their own skilled employees that share similar sustainability-oriented values enabled the case companies to deliver their high-quality services. A couple of the case companies had participated in development projects funded or initiated by governmental organisations, through which funding or other support was provided for supporting sustainability-oriented business. Furthermore, Company 9 rented forest land from a governmental organisation to provide the service.

Customers, either other companies, forest owners or consumers, were paying for the sustainability-oriented services and hence part of the economic value creation. In particular, auditing companies were in a central role in income generation, since they verified the environmental or climate compensation in practice. Most of the case companies also required resources from other companies. Large forest companies particularly created the demand for the service for those case companies operating within the wood-based business sector, whilst forest owners sold the necessary wood. For most of the case companies collaborating with stakeholders such as research organisations, governmental organisations, lobbying organisations, NGOs or their own employees enabled business development.

3.3.2 Sustainable value creation for stakeholders

Interviewees considered nature an essential stakeholder, for which value was created in the sustainability-oriented services. Thus, nature was restored, regenerated or preserved through many of the services. In addition, the carbon sequestration of forests was enhanced. Direct environmental value was created by e.g. restoring water ecosystems and their habitats affected by forest draining and by reforesting areas such as old fields and wastelands. In several case companies, biodiversity was enhanced indirectly, for example, by prolonging forest rotation length, leaving more trees in harvests (e.g. through continuous cover forestry), utilising more tree species, and overall managing or utilising forests less as compared to business-as-usual models. Hence, customers were one of the main stakeholder groups for which environmental value was created, as addressed by one interviewee:

“Well, we aim at fulfilling our customers’ wishes that they want to take care of nature as well.” (Company 6)

Hence, in most of the case companies, environmental activities were performed due to customers’ desire to enhance their environmental/climate footprint or performance, or compensate their negative environmental effects; e.g. Company 5 enabled circular economy-based patents, processes and services for its customers and Company 6 and 9 enhanced their customers’ human-nature relationship, which would accumulate within time within their personal lives and the surrounding nature. In Company 9, nature rights were acknowledged and taught to customers.

Other important stakeholders such as companies, governmental organisations and research organisations had benefited from the empirical sustainability knowledge, methods and processes developed. Forest owners had gained knowledge and new services for climate and environment-based forest planning, management or ownership. Company 2 enabled environmental NGOs to distribute private donations to nature restoration. Overall, many case companies had been able to provide work possibilities for other people with similar sustainability-oriented values.

Forest owners were considered as important stakeholders for whom social value was created, and thus for whom alternative sustainability-oriented services had been developed compared to prevailing forest-based services. Hence, forest owners could gain income and keep their private ownership, but without practising conventional forest management by, e.g. selling carbon storage credits. Longer rotation times and certification would also provide higher income for them. Thus, some interviewees mentioned that they were on the side of the forest owners, which was considered to be neglected in the conventional large-scale forest-based business. Consequently, enhancing the transparency of the operations and prices to forest owners was emphasised in many services, as noted by one interviewee:

“And today’s trend is that everything is outsourced: large companies do not have their own employees but have sub-contractors instead. And then they have long (sub-contractor) supply chains. And we have been gaining benefit from it, since we have a transparent supply chain. There is no one else between the customer and the employee (forest worker) but us.” (Company 8)

Also, recreational values of forests in forest planning were brought forward for forest owners in Companies 4, 6 and 8. In addition, Company 8 was providing longer terms of payment for forest owners to support their livelihood, whilst for Company 6 providing low prices enabled any forest owner to afford the services.

The customer perspective for social value creation was emphasised overall by some case companies. For instance, Company 9 promoted equal rights to as well as health and safety in forests and provided information on planetary diet and living habits to their customers, Company 3 provided guidance on the regulative environment to their customers, and Company 5 enabled circular economy solutions to their customers by providing circular processes fostering new-purpose uses for recycled wood. Other companies were seen to benefit from social value creation, e.g. as new business collaboration possibilities, enhanced wellbeing gained from nature-oriented gifts, and enhanced social reputation. Research organisations’ benefits related to new research topics or knowledge generation. Social value creation for employees related to being able to work in an organisation which corresponds with personal values and to gain long-term employment and higher salaries than in competitor companies; especially compared to large companies, which tend to favour contracts with sole traders and subcontractors. Company 6 had been able to provide employment opportunities for people with varying backgrounds (even though, due to the unfavourable business environment, they had had to lose some of them). More societal stakeholders were also emphasised as beneficiaries by some companies including rural communities and other users of forests. According to Company 5, by creating economic wealth in rural areas, they can also enhance social wellbeing. Recreational users were seen to benefit from environmentally oriented forest management. Company 6 was keen on providing a sense of community through their business, by creating an environment where both customers and citizens can discuss forests and nature. Hence, they organised forest-related activities with the long-term unemployed as well as workshops in forests with children, whilst providing nature-based education.

In many of the case companies so far, sustainability-oriented services were part of a larger service portfolio, and hence main revenues were gained from other, more business-as-usual types of services. However, for a few companies, the sustainability-oriented services offered made up the main business. In particular, other companies were benefiting economically from the business; e.g. contractors, auditing companies and other companies providing resources. Several companies were striving to combine economic and environmental benefits simultaneously. For instance, companies offering continuous cover forestry services were focused on wood production and hence creating economic value for the company and the forest owner, even though this can sometimes be environmentally friendlier than even-aged forestry. One interviewee concluded:

“So there isn’t this either-or conversation, that do we go with the economy or nature at the front, we can go both at the front and at the end of the day they aren’t that badly in contradiction with each other, but it requires a lot of work.” (Company 4)

Company 5’s customers had improved their efficiency due to the circular services provided. Forest owners had benefited economically from the services, e.g. as shared economic risk with other forest cooperative partners (Company 4), gained alternative income models for forest ownership (Company 1) as well as transparent income generation (Company 8). Finally, employees earned salaries for working in the case companies. In most of the companies, pricing of the sustainable services was rather competitive, and hence in the mid-range. In some case companies where the services were more expensive compared to competitors, the companies justified this by higher quality and design, and this had had to be justified for some customers as well. However, it was acknowledged that it can be difficult to make the higher prices related to sustainability-oriented services visible for customers. A few interviewees mentioned that they cannot compete with the prices of large companies and therefore need to compete with quality as well as customer experience and satisfaction.

3.3.3 Verification of sustainable value creation

The case companies were asked to elaborate how sustainable value creation is verified. Overall, the orientation towards sustainability verification was positive, and they had adopted somewhat similar standards such as PEFC and FSC and other reporting schemes. One interviewee concluded:

“All these certification requirements, it comes from the backbone when we operate in the forests.” (Company 8)

Company 5 was using Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) reporting. Company 3 was already adopting EU’s sustainable finance taxonomy, even though they had not needed such financing. Company 9, providing intangible services, used customer assessment questionnaires to verify, e.g. the sustainability impacts of the service. Those case companies related to carbon sequestration noted that there exists no sufficient certification scheme in Finland, even though they considered it crucial for the business. For many case companies, it was important to enhance transparency. According to one interviewee, verification schemes signal companies’ activeness to the community. In particular, those case companies that used contractors in the forest operations considered it important to verify sustainability. Increasing green washing and large companies’ standards were the main reasons for practicing certification. However, couple companies considered certification schemes insufficient and preferred to audit their own sites. Social aspects were not followed as thoroughly or consciously as environmental, though, e.g. in some standards social aspects are entailed.

4 Discussion

4.1 Internal capabilities and external processes shape sustainable value creation

The nine companies studied represent sustainability-oriented SMEs that create sustainable through various forest-based services. Based on the results, both the operating environment and entrepreneurial orientation of the companies are entailed with respect to how they create sustainable value with and for their stakeholders (Fig. 1). The current operating environment does not seem ideal for the sustainability-oriented SMEs’ development, whereas intrinsic capabilities have enabled them to create sustainable value and adapt to the changing business environment. The three literature-based dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation (innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactiveness) are present in the ways how the companies create sustainable value. Similar capabilities have been recorded in other sustainability-oriented SMEs as well (Cullen and De Angelis 2021). In addition to these capabilities, the investigated companies were positively oriented towards future. Simultaneously, changes in the operating environment, especially those related to sustainability transition, have created a momentum for these companies to emerge. Hence, these sustainability-oriented companies are proactive in adapting to the changes in their operating environment and seizing opportunities arising from sustainability challenges (Knoppen and Knight 2022). They address sustainability challenges seriously but simultaneously as something to be solved. Hence, this research also supports the argument of Alcalde-Calonge et al. (2022), according to which both companies’ external and internal aspects are important for sustainable value creation. Furthermore, extending the prior research, this research emphasises the role of sustainability-oriented SMEs and their internal capabilities in transforming their operating environment, e.g. through participating in governance development (Loorbach and Wijsman 2013). The results of this study imply that the relationship between the operating environment and companies’ entrepreneurial orientation is two-directional. The operating environment and related changes exerted a great impact on the companies’ value creation and hence they were open to new ideas and eager to continuously develop their business as based on the changing business environment. Simultaneously, many companies participated actively in legislation and policymaking, and they were perseverant in practicing their business despite the resistance from the established structures of the business environment. Thus, the operating environment strongly impacts how such businesses develop and create value (Alcalde-Calonge et al. 2022). Nevertheless, such entrepreneurially oriented companies are active in transforming their operating environment. The ability of SMEs’ to react fast to changes whilst being able to gain a competitive advantage from sustainability has been reported before (Jansson et al. 2017).

Based on the results, there are some features in the operating environment that exert stronger impact on the sustainability-oriented SMEs and their value creation. First, the role of regulation and governance as well as the established forest-based sector in Finland were emphasised in the interviews. The role of regulation and policies is thus critical: at best, they support founding such sustainable businesses, but at worst they prevent them from developing. Hence, new policies including supply chain due diligence, carbon and environmental pricing, and animal and nature rights are required (Konietzko et al. 2023). Secondly, most of the case companies considered the established Finnish forest-based sector and the large companies dominating it as detrimental to the sector’s development. For instance, the large companies opposed some of the new sustainable business models of the SMEs: they criticised transparent pricing and affected the competition negatively by using unskilled and underpaid employees through outsourcing. One reason for this could be that large companies see sustainability-oriented SMEs as competitors and a threat to their established value creation logics, through which low value-added products are produced for international markets (Laakkonen et al. 2023). However, this was also considered an important motivation for the development of new sustainable business. According to Cohen and Winn (2007), market imperfections such as inefficient firms, externalities, flawed pricing mechanisms and information asymmetry provide significant opportunities for the emergence of such sustainability-oriented companies. The large companies could be in a gatekeeper position, either as supporting or hindering new companies to emerge: therefore, collaborating with large companies could be beneficial for SMEs entering the circular bioeconomy (Jernström et al. 2017). The final crucial aspect is the role of sustainable finance. For instance, one company had not received a loan as their turnover was insufficient, whilst simultaneously many companies did not desire to take out any loans. Such risk-avoiding behaviour has been reported in prior research related to sustainability-oriented SMEs (Lumpkin et al. 2013). This could indicate that no suitable financing for such sustainable businesses exist and hence developing them would require new knowledge from decisionmakers as well (Callegari and Nybakk 2022). Furthermore, this elicits the question as to whether sustainability-oriented business can be effective enough without external financing.

Another important finding of this study relates to the connection between entrepreneurial orientation and sustainable value creation. Entrepreneurial endeavours and sustainability do not always match. This separated the companies from each other and thus some companies were more growth-oriented than others. For these companies, sustainability was more of a competitive advantage (Knoppen and Knight 2022) than a true endeavour itself, whilst giving the impression that sustainability could be replaced with another topical issue. Cullen and De Angelis (2021) noticed that prioritising sustainable value creation challenges scaled up the business, and hence these values could lose their focus in the company’s value creation logic. This brings out the fundamental question of what the true motivation for sustainable entrepreneurship is – economic benefits through sustainability improvements or prospering natural environment and society. According to some of the case companies, such a triple-bottom line, a win-win-win situation, could be gained. Hence, the difference between these companies’ entrepreneurial orientation and sustainability-orientation could be explained by their “embeddedness” to a wider system for which value is created (Cullen and De Angelis 2021). Such embeddedness could not be reported in all the companies. The findings of this study confirm that stakeholders both contribute to and benefit from sustainable value creation (Freudenreich et al. 2020). Thus, based on the company views, most of the case companies’ stakeholders seem to share a joint goal of improving the state of natural environment (Freeman 2010; Freudenreich et al. 2020), though some governmental organisations in particular (related to policymaking) and large forest-based companies appear to lack this vision. Nature seems to be one of the main stakeholders for which value is created, yet environmental value creation requires resources (both tangible and intangible) from several stakeholders. This can also be seen as mitigating risks through which a company can specialise in providing its own niche expertise. In some companies, the natural environment was often used as a resource pool for value creation instead of it being an active agent in value creation. Nevertheless, according to the Company 1’s business model, main activities related to providing a habitat for other animals and species by restoring peatland ecosystems. A similar idea of having a partnership with nature (Konietzko et al. 2023) was also present in Company 7’s tree-planting service and Company 9’s forest-related health care service.

It appears that some essential stakeholders for sustainable value creation are also missing from the companies’ networks, e.g. forest owners that are willing to pay for restoration activities or funding agencies that have sufficient funding instruments for sustainability-oriented SMEs. Stakeholders can also contribute to value destruction or other tensions and conflicts (Tura et al. 2019; Manninen et al. 2023), such as in the cases of carbon sequestration-based companies for which the Finnish government has not been able to make fundamental decisions on carbon credit accounting. There was very little if any value co-creation with large forest companies: instead, they related more to value destruction. This could be a central issue for the development of such sustainability-oriented SMEs as well as the sustainability transition of the forest-based sector overall. In addition, value co-creation with similar sustainability-oriented companies was missing, though they could benefit from mutual co-learning and knowledge sharing.

Social value creation included multiple aspects from individual to societal levels, e.g. enhancing employment possibilities, rural or local development and diverse forest ownership. Hence, customers such as other companies and forest owners were, in particular, the main stakeholders for whom social value was created. Despite this, based on the companies’ views, it seemed more secondary compared to environmental value creation, even though versatile aspects were included. Only two case companies focused on enhancing human-nature relationships. Hence, it seems that the companies have not configured their businesses’ societal impact thoroughly, despite the fact that they are collectively contributing to transforming the forest-based sector towards a more sustainable model and their societal impact is subsequently substantial. They promote collectively more sustainable and versatile use of forests as well as better working conditions and well-being related to forests, hence providing innovations for society and enabling other sustainable businesses to emerge by, i.e. creating positive externalities (Cohen and Winn 2007). Furthermore, they are cohesively widening the perception of the traditional forest-based sector, its boundaries and related services, thereby linking it to other sectors as well.

Even though nature as well as societal or social aspects to some extent were important stakeholders for which value was created, several companies emphasised economic aspects in value creation, either for themselves or their stakeholders. Some were aiming at gaining and maximising income from forests, which is quite evident for the initial purpose of these businesses – maximising profits for the shareholders. Two interviewees were striving for an exit strategy, i.e. growing and selling their business fast, which can often contradict environmental and social aims (Edwards 2021). Hence, only a few of the case companies could be considered creating “truly” sustainable or regenerative value (Dyllick and Muff 2016; Konietzko et al. 2023), i.e. creating net-positive effect to environment or society. For some companies, sustainable value creation was related to specific services, while also simultaneously providing more conventional business-as-usual type services. This finding complies with those of St-Jean and Le Bel (2010), according to which entrepreneurially oriented forest-based companies chose diversification as their main strategy. Hence, such strategy seems optimal for sustainability-oriented companies as well for which established markets do not exist. However, this can be interpreted as risk-avoiding behaviour, which differs from entrepreneurial orientation.

4.2 Managerial implications

This study has several recommendations for business managers and other practitioners. Firstly, this multiple-case study has provided a more comprehensive definition and understanding of sustainable value creation, which to date has been ambiguous and understood differently by various actors. The second implication relates to stakeholders. Companies can respond to sustainability challenges through their business activities by creating sustainable value with their stakeholders. Furthermore, creating environmental value can benefit social value creation and vice versa, whilst contributing positively to economic aspects such as, e.g. efficiency and cost reductions. Since environmental value creation is often in the focus of today’s sustainability-oriented businesses, managers could develop the social and societal impacts of their businesses further. Furthermore, enhancing women entrepreneurship and leadership could result as new sustainable businesses based on intrinsic values of forests and human-nature relationships. Another important aspect relates to how sustainable services are marketed. Marketing should include verified examples of value creation and other experiences to avoid green washing. Enhanced marketing could also benefit sales and consumers’ awareness of sustainability-oriented services, which has still been rather moderate. This implication also relates to enhancing SMEs’ networking skills, since this could be crucial for their development. Such companies share synergies and could benefit from value co-creation, through which new innovations for sustainability could emerge.

4.3 Theoretical implications

This research has several contributions to strategic management and entrepreneurship research, especially within the context of natural resource-based industries. The environmental aspects of SMEs have been particularly addressed in past research (Klewitz and Hansen 2014), and this research has therefore taken a holistic approach to sustainability. The research shows that both the entrepreneur’s intrinsic orientation (Andersén et al. 2015) and external environment (Alcalde-Calonge et al. 2022) affect how sustainable value is created. Furthermore, it is argued that the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and external environment is two-directional, and therefore sustainability-oriented entrepreneurs are not only responding to changes in the operating environment but also contributing to develop it. In addition to the traditional elements of entrepreneurial orientation – namely innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking – this research also suggests ‘future orientation’ as an additional element. This research has provided a more nuanced understanding of sustainable value creation with and for stakeholders (Freudenreich et al. 2020). Yet, it is argued that such a stakeholder approach to sustainable value creation (Upward and Jones 2016) with a focus on human or human-related relationships tends to somewhat neglect the natural environment as a stakeholder with an agency in value creation. Therefore, a combination of the triple bottom line and stakeholder approaches to comprehend sustainable value creation is supported. The research shows that sustainable value creation is strongly context specific and hence environmental and social aspects differ between industries and regions. However, of specific focus should be the scale of responsibility, i.e. understanding the tensions between local and global aspects in doing sustainable business. Hence, sustainable business model design is a matter of considering planetary boundaries, local circumstances, and stakeholder needs (Konietzko et al. 2023). Finally, in the field of forest sciences, this research supports the diversification of the concept of forest-based services (Pelli 2018), through which sustainable value can be created.

4.4 Limitations

Even though the data from this qualitative multiple case study generate important understanding on the relationship between the company’s entrepreneurial orientation, external environment and sustainable value creation, the results cannot be directly generalised to a broader population. Hence, the research represents interesting examples and various impressions and angles of sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship through which new insights for future research can be gained. In addition, a rather small number of case companies could be considered as a limitation, however, there are not many companies in Finland representing such forest-based sustainable value creation. Even though the scope on forest-based business could have entailed other natural resources as well, forest-based business represents a unique business field with an established business environment as well as actors and laws. Another limitation stems from the interpretation of the interview data, especially related to sustainable value creation. Some of the interviewees discussed their aspirations for the value creation instead of describing their realised business activities. Hence, in the data analysis phase, the researchers had to carefully separate these two perspectives from each other. In addition, it would be necessary to interview the case companies’ stakeholders to gain a more profound understanding of sustainable value creation, though this was not within the scope of this study.

5 Conclusions and directions for future research

Sustainability transition in the forest-based sector calls for sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship through which environmental and social issues can be tackled. However, there exists a gap between practice and theory on how both entrepreneurial processes and external environment of sustainability-oriented SMEs shape their sustainable value creation. Furthermore, empirical examples of companies creating sustainable value have been lacking. Hence, this multiple case study has investigated nine Finnish sustainability-oriented SMEs providing forest-based services and the relationship of their external environment and entrepreneurial orientation on how they create sustainable value with and for their stakeholders. The companies investigated possess several entrepreneurial capabilities that enable them to create sustainable value. Furthermore, the operating environment can at best support the emergence and long-term development of sustainable businesses and innovations, and hence collaboration with stakeholders is essential for sustainable value creation.